Peace-building, Conflict transformation and Reconciliation through Second Track Diplomacy and Soft Politics

A. Ways of action

The absence of war does not mean sustainable peace. While the nations and the communities involved in the conflicts have abided to the internationally brokered peace agreements, in depth they have still not accepted each other’s differences. The most obvious situation is present in Kosovo where Serbs are practically “banned” from existing both politically as well as culturally or religiously.

By enforcing non-conventional diplomatic practices through non-state actors, one can move from rejection, disintegration, segregation and isolation to acceptance, understanding, celebration and integration in societies torn by internal ethnic and religious conflicts such as the Western Balkans, Caucasus or the Mediterranean/Middle East.

Four main second track diplomacy lanes can be identified:

1. Faith-based diplomacy: is aimed at identifying religious texts, ideologies, practices, and the traditions of oftentimes competing or conflicting ethnic groups, because of a potential integration between religion and politics. In the Balkans the conflicts of the 90 were not just territorial and state related but also identity conflicts related to religion. Even today in the Balkans people refer to one another based on religion, not ethnicity. Serbs are referred to as Orthodox, Croats as Catholic and Bosnian as Muslim. The only ones mostly referred to as ethnically are Albanians. Politics and religion are closely linked in the Balkans. Croatia was making a case for EU integration based on the fact that it is the only Catholic nation in Europe outside the EU, Serbia and Greece have strong ties due to their Orthodoxy, Turkey supports Albania, etc.

Religious organizations also make efforts to overcome religious-intolerance, sectarianism or nationalism, and to develop an ecumenical climate. Hans Küng urges, as a first step, the development of an ecumenical and concrete theology for peace between Christians, Jews and Muslims (Küng, 1990). A systematic analysis of their divergences and convergences, and their potential of conflict and cooperation would be a helpful step forwards.

Concrete actions: establish inter-faith dialogue though discussions, seminars, conferences

Non-state actors: leaders of all faiths involved/churches, NGOs, educators/schools/universities, think-tanks, research institutes.

2. Cultural diplomacy: is aimed at identifying cultural patterns of behavior as well as the commonalities of two or more conflicting groups in order to find a common ground of dialogue while preserving culturally sensitive aspects. Sharing culture leads to mutual understanding and acceptance of the other’s identity.

Concrete actions: cultural events such as European Cultural Capital, celebrating diversity by exhibiting art belonging to all ethnic groups involved,

Non-state actors: cultural Institutes, NGOs, educators/schools/universities

3. Education - languages, translation and subtitles: Becoming aware of ones language is a first step towards reconciliation. In the Balkans, the artificially created Serbo-Croatian language was and still is a thorny issue. Although the two languages are very much alike, as an aftermath of war the two countries insist they speak a different language, Serbian and Croatian. Bosnian is one of them, while Albanian is a totally different language. There are also many dialects along the Adriatic coast, as well as in the rural areas of the Balkans. Proper translation of written materials, history books, school manuals and subtitling of movies in each language of the region is a powerful reconciliation tool.

Concrete actions: film festivals in all languages, fund raising for subtitling movies in languages of the region. Same works for children books in mixed schools. Bi-narrative history books are also an option worth exploring following the French-German model.

Non-state actors: cultural Institutes, NGOs, educators/schools/universities, the movie industry, the publishing industry

4. Business cooperation and economic diplomacy: probably economic incentives are the strongest reconciliation tool that exists, provided that they are applied non-discriminatory and equally to the conflicting parties. Oftentimes ethnic and religious conflicts have an economic component such as poverty, unequal distribution of resources, or are actually a conflict over resources but disguised in an ethnic or religious one. The involvement of the corporate world in reconciliation and peace building is essential. If we look at South Africa, the end of the Apartheid was driven in the first place by white powerful business leaders. Businesses have a lot to lose from conflicts and instability. With the exception of the arms industry which is a direct contributor to war, the majority of businesses gain from a stable and constructive environment.

Concrete actions: joint ventures, foreign investments, creating jobs on equal basis, supporting the SME cross-nationality, building a public-private partnership, natural resource management with the equal involvement of local actors.

Non-state actors: Commerce and Economic Chambers, the “Balkan” diasporas, local businesses, multinational corporations.

Other actions should include encouraging policy consideration of issues extending beyond peace implementation, such as democratization and the development of a civil society, identifying ways and creating opportunities for citizens of all faith and ethnicity and their leaders to assume responsibility for the peace process an exploring prospects for entire regions to cooperate in building a just, stable and prosperous environment for all its citizens.

2. Implementation

Second-track diplomacy should be complementary to official diplomatic peace building and reconciliation efforts and accompany them in all fields. Peace-building and reconciliation are a multifaceted and complex process which needs the convergence of conventional and non-conventional practices.

Smart power (the cost effective combination of soft and hard politics/diplomacy) must be the result of the use of practices such as faith-based, cultural or business diplomacy.

Peace is a learning process. Therefore, track II peace-makers assume that, in many cases, violence and war are the consequence of a wrong assessment of the consequences of war or of a lack of know-how to manage conflicts in a more constructive way. They also believe that warlike or peaceful behavior is learned behavior, and that what is learned could be unlearned through peace-research and peace-education.

Track II diplomacy involves a series of activities such as 1) the establishment of channels of communication between the main protagonists to facilitate exploratory discussions in private, without commitment, in all matters that have or could cause tensions; 2) setting up an organization which can offer problem-solving services for parties engaged in conflicts within and between nations; 3) the establishment of a center to educate people undertaking such work; and 4) the creation of a research center or network in which know-how and techniques are developed to support the above mentioned tasks.

An NGO with ample experience in constructive conflict management is 'Search for Common Ground' based in Washington DC. It began in 1982 and focused originally on Soviet-American relations. Now it works in the Russian Federation, the Middle East (Lebanon), South Africa, Macedonia and Kosovo and the United States. They develop what they call a common ground approach which draws from techniques of conflict resolution, negotiation, collaborative problem solving and facilitation. The aim is to discover not the lowest but the highest denominator (http://www.sfcg.org).

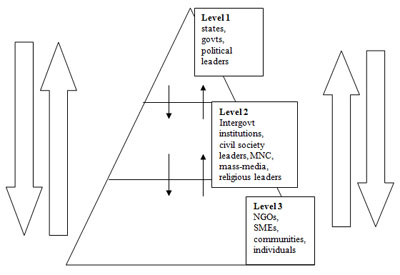

Communication at all levels, internally, subregional/regional, internationally at both the civil society and institutional/interinstitutional, as well as at the governmental/intergovernmental levels is needed in order to disseminate information and implement policy.

A three level action model at state or regional level

At the grass roots level NGOs, small businesses and educational/cultural institutions must act at the people-to-people level to directly empower individuals and communities, at the middle level intergovernmental institutions and civil society leaders must promote and support programs that ensure cross-cultural communication and understanding, and last but not least at the upper level governments and political leaders must agree to work and act towards reconciliation. The three levels must be connected and interact with one another in a two way system in a cross-level manner.

3. Crossing borders, Building bridges. The Role of the EU

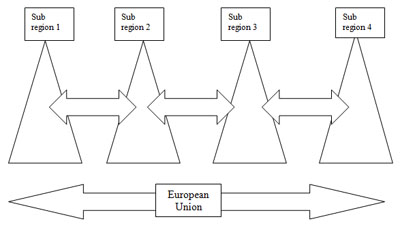

Due to globalization, states can no longer exist individually. Therefore communication must also work horizontally between them not just at the political-diplomatic levels but also at other less conventional levels. Economy is the primary force in this process as economic interdependence is a proven fact, but levels such as culture and education must also be approached. The EU is a good model in this respect.

The Balkans, the Caucasus and the Mediterranean have many things in common. A mix of ethnicities and religions, rich histories and cultures and they have all been torn apart by war, dictatorships or frozen conflicts.

But these regions have another thing in common: great potential for development.

An invisible line may connect the Mediterranean/Adriatic area with the Caspian Sea in a symbolic bridge and identify areas where track two diplomacy can act. Each foot of the bridge represents a pillar for stability and the bridge itself a path to transfer knowledge.

At smaller sub-regional levels (for example inside the Balkan region itself) smaller connections can be made at the horizontal levels.

The role of the European Union

The EU is the only unitary structure which has a vast diversity of languages and cultures, and yet it presents itself as a homogenous entity. Because of this combination it can build bridges by preserving the soft political aspects of each region, sub-region and country.

International IDEA (Democracy in Development: Global consultations on the EU’s role in democracy building, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2009) advances the following: The EU must be ready to accept democratic outcomes from within. Today it seems to be widely recognized that democracy cannot be brought about in a top-down and outside-in way. This recognition urgently needs to be translated into true dialogue between peers in a way which is active but not aggressive, critical but not condescending, honest but not humiliating.

The need for new approaches to democracy building is further underscored by continuing global political and economic power shifts. The message from partners is that the EU is well placed to take a leadership role in shaping new approaches. The EU is seen by counterparts in other regions as arguably the biggest democratic success story in history. It is seen as an attractive and reliable cooperation partner, marked by long-term commitments and a transparent agenda. The EU’s own internal achievements are frequently held up as a source of inspiration: peace, democracy, economic development, social cohesion and regional integration.

But dialogue must present direct benefits to the partners, not just to the EU. Therefore the EU must do the following:

1. The EU needs to articulate its own experiences of democracy building, in order to respond to the great interest in the EU story and to inspire political dialogue and shared learning across regions by sharing its own history.

2. The EU needs to reflect its internal achievements in its external action. The broad understanding of democracy as integrating political, social and economic rights which has been so successful in Europe itself, should be reflected in the EU’s external action as well. Such an effort will require more interconnectedness between policy areas within the EU.

3. The EU needs to stand by its basic principles, reaffirming its long-term commitment to democracy even in situations where short-term interests might lead to difficult compromises and avoid double standards.

4. The EU must turn its rhetoric of partnership into a reality perceived by partners if progress on democracy building is to be achieved. Partnerships not preaching, dialogue not declarations.

Works

http://www.caosmanagement.it/n41/art41_09.html

- România spre Uniunea Europeană. Negocierile de aderare (2000-2004), Iaşi: Institutul European, 2007

- România şi iar România. Note pentru o istorie prezentă, Cluj-Napoca: Eikon, 2007

- European Negotiations. A Case Study: The Romania’s Accession to EU. Gorizia, IUIES, 2006

- “Sticks and Carrots”. Regranting the Most-Favored-Nation Status for Romania (US Congress, 1990-1996) / “Bastoane şi Morcovi”, Reacordarea clauzei naţiunii celei mai favorizate (Congresul SUA, 1990-1996), Cluj-Napoca: Eikon, 2006

- Relaţii internaţionale/transnaţionale, Cluj-Napoca: Sincron, 2005

- Negociind cu Uniunea Europeană, 6 volume, ed. Economică, Bucureşti, 2003:

- vol. I - „Documente iniţiale de poziţie la capitolele de negociere” (2003)

- vol. II – „Initial Position Documents” (2003)

- vol. III – „Preparing the External Environment of Negotiations” (2003)

- vol. IV – „Pregătirea mediului intern de negociere” (2003)

- vol. V – „Pregătirea mediului de negociere, 2003 – 2004” (2005)

- vol. VI – „Comunicarea publică şi negocierea pentru aderare, 2003 – 2004” (2005)

- Universitate-Societate-Modernizare, Presa Univ. Clujeană, Cluj-Napoca, 1995; Ediţia a II-a, 2003

- Speranţă şi disperare - Negocieri româno-aliate, 1943-1944, Bucureşti, Ed.Litera, 1995; Ediţia a II-a, 2003

- Relaţii internaţionale contemporane, Cluj-Napoca, Sincron, 1999; Ediţia a II-a, 2003

- Căderea României în Balcani, Cluj-Napoca, Dacia, 2000

- Pulsul istoriei în Europa Centrală, Cluj-Napoca, Sincron, 1998

- Transilvania si aranjamentele europene. 1940-1944, Cluj-Napoca, Ed.FCR, 1995

- Alma Mater Napocensis – Idealul universităţii moderne, Cluj-Napoca, Ed. FCR 1994

- Dr. Petru Groza – pentru o „lume nouă”, Editura Dacia, 1985 (a fost interzisă şi arsă întreaga ediţie)

Vasile Puşcaş: è deputato rumeno del Parlamento Europeo membro del Gruppo Socialista. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasile_Pu%C5%9Fca%C5%9F : (b. Surduc, July 8, 1952) is a Romanian politician, diplomat and International Relations professor. Biography. During 2000-2004 he was the Romanian Chief Negotiator with the European Union, and he is considered by many "responsible" for Romania's accession to the EU. Currently, he is a member of the Romanian Parliament and a member of the PSD - Social-Democratic Party in Romania. He is highly appreciated both in Romanian political circles and the European ones.

Oana Cristina Popa Current: Postdoctoral European fellow at Romanian Academy; Minister Counsellor at Ministry of Foreign Affairs Romania; Postdoctoral European fellow at Romanian Academy; Associate researcher at Institute for International Studies, Babes-Bolyai University of Cluj.

Past: Ambassador at Romanian Embassy in Zagreb, Croatia; DCM at Emabssy of Romania in Zagreb; Director at Ministry of Foreign Affairs Romania

Education: Harvard University Kennedy School of Government; Universitatea 'Babes-Bolyai' din Cluj-Napoca; American University.

http://ro.linkedin.com/pub/oana-cristina-popa/a/b58/788